Last updated on November 28, 2020

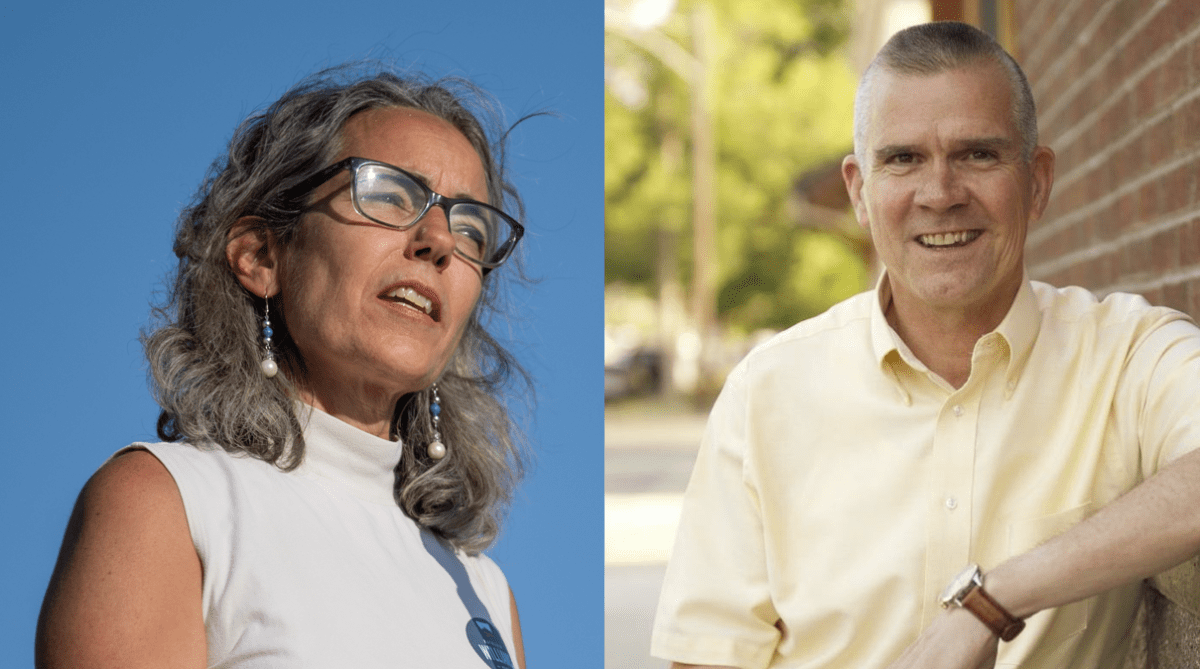

U.S. House candidates Kathleen Williams and Matt Rosendale have made health care central to their campaigns. They may agree on a few details, but their proposed paths forward could hardly be more divergent.

As the coronavirus swept across Montana this summer, infecting thousands of people and disrupting the lives of untold others, the U.S. House race chugged along in the campaign equivalent of second gear. Democrat Kathleen Williams and Republican Matt Rosendale opted against the traditional tire-rubber approach to ginning up voter support, sticking instead to phone calls and virtual meetings. Ads flashed on televisions and computer screens: Williams gutting a fish here, Rosendale shaking hands at an auto shop there.

The season provided a stark contrast to 2018, when both candidates trekked far and wide across the state, Williams in her failed first congressional bid, Rosendale in his unsuccessful attempt to unseat U.S. Sen. Jon Tester. But as the pandemic limited each campaign’s exposure, it also heightened voters’ focus on a core issue in Montana and American politics. Williams and Rosendale wasted no time reacting to the shifting electoral winds. Health care became one of the race’s defining themes.

For Rosendale, that’s taken the form of renewed messaging about repealing the Affordable Care Act, and a push to highlight policy changes made during his term as state auditor. Williams, meanwhile, has built on proposals she outlined in a policy white paper in 2018, including a pitch to lower the Medicare eligibility age from 65 to 55. Each has vowed to be a stalwart voice for Montanans’ best interests when it comes to health care at a time when those interests are at pandemic-heightened risk

Wildfire smoke hung thick in the air above the Gallatin Valley on a mid-September afternoon, obscuring the Bridger Range with a visual reminder of concerns about the long-term effects of such exposure. Williams sat on the back deck of her ranch-style home on the outskirts of Bozeman, reflecting on phone conversations she’d had with voters throughout the summer — conversations, she said, that spoke not only to specific health needs, but to a commonality with challenges Williams has experienced in her own life.

“There was one night where I was calling voters, and in about an hour I had talked to three women who had lost their husbands recently,” said Williams, whose husband, Thomas Pick, died unexpectedly while skiing in the North Absaroka Wilderness in early 2016. “That’s my situation, too. And so to me, being a representative, where you’re grounded in Montanans’ hopes, struggles and dreams, it is not out of bounds for me to say, ‘I hope this isn’t too personal, but do you have resources?’”

The personal touch is an extension of the type of retail politicking Williams honed on the road trips that defined her 2018 campaign. And it pervades every aspect of health care she addresses. Her recommendation for more in-state psychiatric residencies and expanded telehealth options for people with mental health conditions? Inspired by the work of her stepson and stepsister-in-law through a San Francisco-based mental health nonprofit and stories she’s heard from Montanans along the Rocky Mountain Front. Her continued demand for a more strategic approach to COVID-19 testing? Triggered by a chat with a hospital CEO and her own familiarity, after 25 years in Montana and three terms in the state Legislature, with the state’s laboratory resources.

Williams’ path on health care embraces key provisions of the ACA, such as the prohibition on health insurance companies denying coverage for pre-existing conditions, while acknowledging that additional changes to the law are necessary to make health care affordable for all. It’s a path that shares several notable landmarks with Rosendale’s. Both candidates have affirmed a need for expanded telehealth services to better reach Montana’s far-flung rural population, and stated their desire to increase access to direct primary care agreements, which allow individuals to negotiate payments for specific primary care services directly with their physicians.

The latter is turf Rosendale has already laid claim to. Following several unsuccessful attempts by Republican legislators, including then-state-Sen. Rosendale in 2015, to pass legislation allowing direct primary care, Rosendale wielded the power of his post as state auditor and insurance commissioner in 2017 to clarify that such agreements are not insurance products. His memo freed providers offering direct primary care from regulatory consideration and, as Rosendale is quick to say, saved Montanans money.

“We’ve got thousands of people now that are getting high-quality direct primary care for $75 to $95 a month, and purchasing high-deductible hospitalization plans in addition to that, and the combination of those two products are delivering extremely high-quality health care for a fraction of the price that they had been spending,” Rosendale told Montana Free Press by phone. “I mean, they’re saving thousands of dollars, and that is a really, really big deal for the families across our state.”

In discussing specific health policy goals, Rosendale leans on a familiarity with the mechanics of the health care industry sharpened by his time in the insurance commissioner’s chair. Removing contribution limits on health savings accounts and untethering them from insurance products will put spending power in the hands of consumers, he said. And, he said, curbing the authority of pharmacy benefit managers, who manage prescription drug benefits for health insurers, will drive those costs down.

While the two candidates’ paths would seem to converge at the same distant peak, where adequate health care is accessible and affordable for all Montanans, their distinct routes are largely defined by the point at which they diverge: the Affordable Care Act.

The Williams approach involves additions to the massive reform bill passed in 2010, and a revisitation of some of the thorny issues that were either discarded or avoided in the interests of bipartisan cooperation — in other words, methodically building on the existing framework.

“It takes candidates and representatives that know what questions to ask, that have experience working in health care policy,” Williams said, referencing to her own work as a legislator carrying a 2011 bill benefiting cancer patients. “My background is in natural resources, but I was working on health care policy in the Legislature, forcing insurers to stop denying routine care to cancer patients.”

Rosendale proposes a trickier ascent, one that wipes the ACA off the map entirely in favor of a new route that Republicans to date have not charted. It’s an approach that fits the hard-working, system-bucking brand Rosendale has built for himself through several election cycles. But such a route will likely sacrifice ground early on, and steepen Congress’ climb by necessitating new measures to preserve or replace cost-saving initiatives Montana has already implemented under the auspices of the ACA. These include Medicaid expansion, which had 86,533 adult enrollees as of Aug. 1, and Montana’s reinsurance program, which Rosendale continues to highlight as one of his crowning achievements in reducing in-state health insurance premiums.

Rob Saldin, a political scientist and professor at the University of Montana, isn’t surprised that the complicated and often divisive issue of health care policy has taken center stage in the U.S. House race. Personal health being at the forefront of voters’ minds now makes the prevalence of health care in the 2020 election cycle inevitable. Even beyond the pandemic, it’s a topic that benefited Republicans when public opinion of the ACA was low, and that in 2018 swung back in Democrats’ favor as the ACA’s favorability ratings climbed.

“That’s certainly an issue that the Williams campaign has actively sought to make one of the issues in the spotlight,” Saldin said. “But it’s also natural in the sense that Matt Rosendale is the state auditor, which places him right in the middle of that issue.”

A September New York Times poll of 625 likely Montana voters put Williams ahead of Rosendale 44% to 41%. Forty-nine percent of respondents also stated a very or somewhat favorable impression of Williams, while 44% said the same for Rosendale. The Times did note a significant flaw in the poll: it included Green Party candidates who, due to recent court rulings, will not appear on the November ballot. Saldin said that likely increases the lean toward Williams.

The poll didn’t include any questions specific to health care, and Saldin was reluctant to speculate about how much the issue may have shaped poll responses.

The pandemic’s interruption of the campaign ground-game came to end this fall, with Rosendale appearing at events including a Belgrade rally with Vice President Mike Pence and Williams launching a six-day, 24-town “Solutions Tour.” The impact of those lost months is nonetheless significant, Saldin said, and was perhaps felt more by Williams, given how central her cross-state treks were to building name recognition in 2018. Rosendale, comparatively, has become a “household name,” Saldin said, having appeared on the ballot in statewide races in each of the past four cycles: in the 2014 Republican primary for U.S. House, in 2016 for state auditor, in 2018 against Tester, and now in his second U.S. House bid.

Public stumping about health care has become a central part of both candidates’ political identities, but some experts caution against focusing too narrowly on any particular issue in an election year. As Dr. Benjamin Miller, a clinical psychologist and chief strategy officer for the national health foundation Well Being Trust, outlined for MTFP, no single policy or initiative is going to mend the still-broken health care system in the United States. Direct primary care agreements are “a great idea,” he said, but they’re not a replacement for insurance. Expanding access to Medicare may be great for some Montanans, he continued, but key flaws in the program limit its usefulness for certain life-saving health services. These programs are just pieces of a complex jigsaw puzzle, and each fills in only a small part of the bigger picture.

Among the many pressing issues Miller said need to be addressed, nationwide and in Montana, is the soaring rate of “deaths of despair” and deaths resulting from addiction and suicide. According to the Well Being Trust’s latest “Pain in the Nation” update, published in May 2020, Montana was among five states where opioid overdose death rates increased more than 15% between 2017 and 2018. The most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control put Montana’s 2018 suicide rate at third-highest in the nation — 24.9 deaths per 100,000 residents.

“All of these things were really bad, and then COVID hit, and what it’s done is it’s exacerbated some of the issues that we knew were driving despair: loneliness, isolation, economic decline, unemployment,” Miller said, referencing another Well Being Trust report released in May that estimated Montana could see 167 additional deaths of despair over the next decade resulting from the pandemic.

It’s on the subject of mental health that Miller’s greatest concern runs headlong into the most significant health care divergence between Rosendale and Williams. Tens of thousands of Montanans have received inpatient and outpatient care for mental health services under Medicaid expansion, a source of coverage made possible only under the ACA.

Ultimately, Miller said, fixing current shortcomings in mental health services and in America’s health care system as a whole calls for a methodical, multi-pronged game plan. And public opinion reflects voters’ desire for detail-oriented reform. While annual polling by Gallup shows that 51% of Americans have a “very” to “somewhat” positive view of the health care industry, concerns deepen the more focused the questions become. Fear that a major health event could throw a household into bankruptcy rose from 45% to 50% between early 2019 and July 2020 — and among non-white adults in particular, from 52% to 64%.

From a health policy standpoint, Miller said, the best thing voters faced with such options can do is look beyond the “fragmented, fractured and frustrating care” that defines the current system and imagine a vision of what health care should look like.

“If we don’t have a vision of what ‘good’ could be and how much better it could be, then we’re never going to be able to advocate, to speak out, to show up, to even question what policies might come our way,” Miller said.

Rosendale and Williams have both sought to position themselves as the most action-oriented option for voters, pointing to their respective records to claim ground already gained in the fight to make health care more robust, more affordable and more accessible. It remains to voters to determine which candidate’s path is most likely to reach the destination.

This article was initially published at MFPT

Be First to Comment